If you have ever listened to Caribbean Rhythms, you have heard BAP discuss various novels: The Red and the Black (Stendhal), Journey To The End Of The Night (Celine), The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With The Sea, Spring Snow (Yukio Mishima), The Man Without Qualities (Robert Musil), Bel Ami (Guy de Maupassant), Storm of Steel, Eumeswil, On the Marble Cliffs (Ernst Jünger ), Nostromo, Lord Jim (Joseph Conrad), and many others. I have read and enjoyed many of these novels and found some comfort in the company of Julien Sorel and Noboru Kuroda, for in these figures, a young man discovers that he is not alone, that his frustration with the mundane stasis of bourgeois society, his desire to break free from the prim, airless world of blue deft tea cups, lace parasols, and velvet sitting rooms where ladies waft white fans and lounge in blue jacquard, is not new in the human heart. Indeed, the young man discovers that he belongs to an illustrious tradition, “a race of men that don’t fit in, a race that can’t stand still.”

In these novels, the spirit of the anarch takes many forms: sometimes the reader meets a roguish Lothario who pierces the listless haze of contemporary society, opposes the strictures of so-called “civilized” society, and ascends to prominence by charming eminent dignitaries or sneaking into ladies’ bed chambers (Bel Ami, The Red and the Black); other times, we encounter a young sailor or sinewy soldier who plunges into an earthen trench or a sea of white foam and emerges, like iron from the flame, hardened and changed (Storm of Steel, Journey To The End Of The Night, and to some extent The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With The Sea). As BAP has noted, these novels are tales of “self-sacrifice for a hidden reality,” “a victory of purity” and “uncompromising spirit” in a fallen and earthly world. They depict the unspeakable anguish of men trapped in a realm where there is “no stage” left for the “noble and heroic heart”1 and relate the stories of a few lonely, solitary men, driven on by a wild, desperate hunger, who set out in search of Elysian fields and the deep, swirling ocean where they might live out their days beside a wide white shore, untouched by sorrow.

But I have said too much already, let us come to the point. I do not intend to furnish lengthy book reviews or reiterate what BAP has already discussed. Instead, I propose a guide for further reading, a list of books that inhabit a similar spirit and likewise deserve a place on the shelf of any sensitive young man. These are books, as Zarathustra said, for “my type among men.” They are, indeed, “fine far-away things” and at them “sheep’s claws shall not grasp!” They are only for sensitive eyes, for men whose native hide is delicate and rare, men who are all too aware of the desolation and spiritual poverty of this modern life. I consider these books to be for the man, like Mishima, who is afflicted with a kind of “romantic agony,” the man who longs for a life of beauty, an elegant past, and a heroic cause but is haunted by the tragic impossibility of the dream, the grim fatality of life, and the “fierce impossible desire to be other than himself.”2

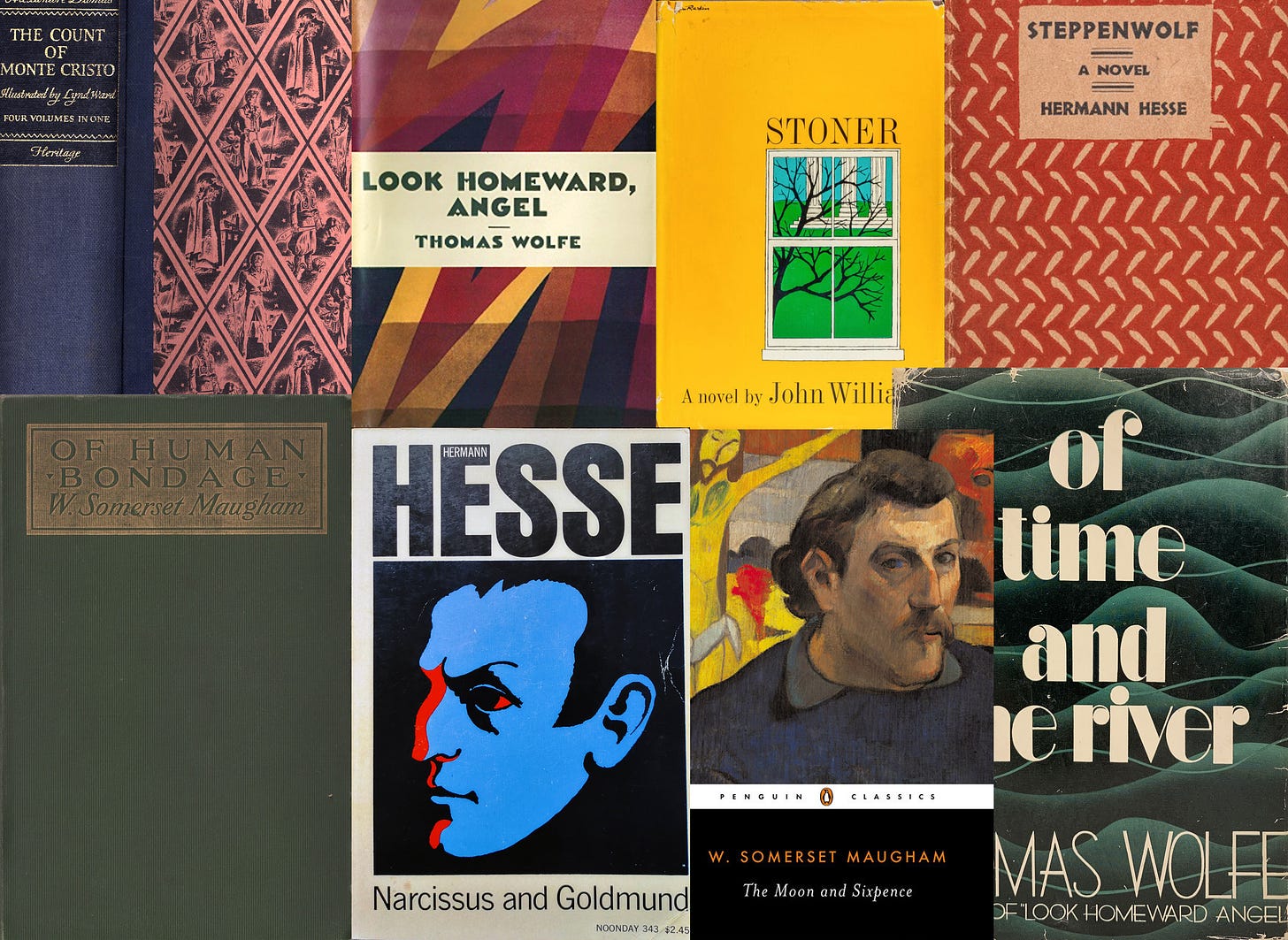

To my knowledge, none of these novels are mentioned by BAP or discussed by the online right (perhaps with the exception of Stoner which has garnered some fame on 4chan). Indeed, few, if any, of these novels carry any professional or cultural cachet. It’s quite possible that few men have even heard of the first four books on this list. I, myself, have never met another living man or woman who has read a book by Thomas Wolfe (not Tom Wolfe) or W. Somerset Maugham (I mention this simply to stress the point that no one will be impressed if you are reading Thomas Wolfe’s magnum opus “Of Time and the River”). The other four books on this list are broadly considered by academics and literary tastemakers to be boyish, juvenile, naively romantic, mawkish, sickening, melodramatic, unrealistic, and—at best—middle-brow. If you mention these books to literary impresarios who arrange autofiction readings, they will probably consider you out of touch; if you try to explain the plot of The Moon and Sixpence to the girl you met at the bar who lives in a luxury highrise and has a SoulCycle membership, she will think you are an insane murderer. All this is to say that if you read simply to get e-girl pussy (understandable) or to impress a group of literary souls who dine at your townhouse every Tuesday evening, stop here. Your time is better spent elsewhere.

This list is FOR MADMEN ONLY.

The Moon and Sixpence (1919), W. Somerset Maugham

Mr. Charles Strickland, an otherwise unassuming businessman of middle age, one day decides that he has had enough of his obnoxious children and his socialite wife, so he decides to abandon his family and leave for Paris (and later, Tahiti) where he paints, has sex with courtesans and native prostitutes, and strives to become a great and dangerous man.

The novel’s title is taken from a critic who, in a review of Maugham’s earlier novel Of Human Bondage, stated that the protagonist, was “so busy yearning for the moon that he never saw the sixpence at his feet.” The Moon and Sixpence addresses the conflict between “the moon” (the timeless and eternal desires of the human heart) and “sixpence” (petty, mundane, earthy concerns, the sterility of civilized life, small change, ladies’ pocketbooks, etc.)

Excerpts:

I have an idea that some men are born out of their due place. Accident has cast them amid certain surroundings, but they have always a nostalgia for a home they know not. They are strangers in their birthplace, and the leafy lanes they have known from childhood or the populous streets in which they have played, remain but a place of passage. They may spend their whole lives aliens among their kindred and remain aloof among the only scenes they have ever known. Perhaps it is this sense of strangeness that sends men far and wide in the search for something permanent, to which they may attach themselves. Perhaps some deep-rooted atavism urges the wanderer back to lands which his ancestors left in the dim beginnings of history. Sometimes a man hits upon a place to which he mysteriously feels that he belongs. Here is the home he sought, and he will settle amid scenes that he has never seen before, among men he has never known, as though they were familiar to him from his birth. Here at last he finds rest.

[…]

Perhaps Charles Strickland was dull judged by a standard that demanded above all things verbal scintillation; but his intelligence was adequate to his sur-roundings, and that is a passport, not only to reasonable success, but still more to happiness. Mrs. Strickland was a charming woman, and she loved him. I pictured their lives, troubled by no untoward adventure, honest, decent, and, by reason of those two upstanding, pleasant children, so obviously destined to carry on the normal traditions of their race and station, not without significance. They would grow old insensibly; they would see their son and daughter come to years of reason, marry in due course the one a pretty girl, future mother of healthy children; the other a handsome, manly fellow, obviously a soldier; and at last, prosperous in their dignified retirement, beloved by their descendants, after a happy, not unuseful life, in the fullness of their age they would sink into the grave.

That must be the story of innumerable couples, and the pattern of life it offers has a homely grace. It reminds you of a placid rivulet, meandering smoothly through green pastures and shaded by pleasant trees, till at last it falls into the vasty sea; but the sea is so calm, so silent, so indifferent, that you are troubled suddenly by a vague uneasiness. Perhaps it is only by a kink in my nature, strong in me even in those days, that I felt in such an existence, the share of the great majority, something amiss. I recognised its social values, I saw its ordered happiness, but a fever in my blood asked for a wilder course. There seemed to me something alarming in such easy delights. In my heart was a desire to live more dangerously. I was not unprepared for jagged rocks and treacherous shoals if I could only have change change and the excitement of the unforeseen.

[…]

Sometimes I've thought of an island lost in a boundless sea, where I could live in some hidden valley, among strange trees, in silence. There I think I could find what I want.

[…]

I don't want love. I haven't time for it. It's weakness. I am a man, and sometimes I want a woman. When I've satisfied my passion I'm ready for other things. I can't overcome my desire, but I hate it; it imprisons my spirit; I look forward to the time when I shall be free from all desire and can give myself without hindrance to my work. Because women can do nothing except love, they've given it a ridiculous importance. They want to persuade us that it's the whole of life. It's an insignificant part. I know lust. That's normal and healthy. Love is a disease. Women are the instruments of my pleasure; I have no patience with their claim to be helpmates, partners, companions.

[…]

When a woman loves you she's not satisfied until she possesses your soul. Because she's weak, she has a rage for domination, and nothing less will satisfy her. She has a small mind, and she resents the abstract which she is unable to grasp. She is occupied with material things, and she is jealous of the ideal. The soul of man wanders through the uttermost regions of the universe, and she seeks to imprison it in the circle of her account-book.

[…]

We seek pitifully to convey to others the treasures of our heart, but they have not the power to accept them, and so we go lonely, side by side but not together, unable to know our fellows and unknown by them. We are like people living in a country whose language they know so little that, with all manner of beautiful and profound things to say, they are condemned to the banalities of the conversation manual. Their brain is seething with ideas, and they can only tell you that the umbrella of the gardener's aunt is in the house.

[…]

He seemed to see his fellow creatures grotesquely, and he was angry with them because they were grotesque; life was a confusion of ridiculous, sordid happenings, a fit subject for laughter, and yet it made him sorrowful to laugh.

[…]

His eyes grew accustomed to the darkness, and now he was seized by an overwhelming sensation as he stared at the painted walls. He knew nothing of pictures, but there was something about these that extraordinarily affected him. From floor to ceiling the walls were covered with a strange and elaborate composition. It was indescribably wonderful and mysterious. It took his breath away. It filled him with an emotion which he could not understand or analyse. He felt the awe and the delight which a man might feel who watched the beginning of a world. It was tremendous, sensual, passionate; and yet there was something horrible there, too, something which made him afraid.

It was the work of a man who had delved into the hidden depths of nature and had discovered secrets which were beautiful and fearful too. It was the work of a man who knew things which it is unholy for men to know. There was something primeval there and terrible. It was not human. It brought to his mind vague recollections of black magic. It was beautiful and obscene.

Of Human Bondage (1915), W. Somerset Maugham

Maugham often described his novels as an attempt to rid himself of persistent memories: “I began once more to be obsessed by the teeming memories of my past life. They came back to me so pressingly, in my sleep, on my walks, at rehearsals, at parties, they became such a burden to me, that I made up my mind there was only one way to be free of them and that was to write them all down in a book.” Of Human Bondage was certainly the most autobiographical of these attempts and contains those memories and emotions closest to Maugham’s own life.

Of Human Bondage follows the growth and maturation of a young orphan, Philip Carey, who is taken in by his aunt and uncle and raised in the vicarage of Blackstable. Philip eventually departs for boarding school and then art school in Germany, seeking some purpose, some great pattern to unite the wild scattered colors of experience and gather together the winding, tattered threads of his life. Philips’s grand struggle “to make a design, intricate and beautiful, out of the myriad, meaningless facts of life” brings him deep into the tumult of the modern world, to Parisian salons and towering cities of iron and cut glass—and there he discovers the meaning of life.

Excerpts:

There are only two things in the world that make life worth living, love and art. I cannot imagine you sitting in an office over a ledger, and do you wear a tall hat and an umbrella and a little black bag? My feeling is that one should look upon life as an adventure, one should burn with the hard, gem-like flame, and one should take risks, one should expose oneself to danger.

Thinking of Cronshaw, Philip remembered the Persian rug which he had given him, telling him that it offered an answer to his question upon the meaning of life; and suddenly the answer occurred to him: he chuckled: now that he had it, it was like one of the puzzles which you worry over till you are shown the solution and then cannot imagine how it could ever have escaped you. The answer was obvious. Life had no meaning. On the earth, satellite of a star speeding through space, living things had arisen under the influence of conditions which were part of the planet’s history; and as there had been a beginning of life upon it so, under the influence of other conditions, there would be an end: man, no more significant than other forms of life, had come not as the climax of creation but as a physical reaction to the environment. Philip remembered the story of the Eastern King who, desiring to know the history of man, was brought by a sage five hundred volumes; busy with affairs of state, he bade him go and condense it; in twenty years the sage returned and his history now was in no more than fifty volumes, but the King, too old then to read so many ponderous tomes, bade him go and shorten it once more; twenty years passed again and the sage, old and gray, brought a single book in which was the knowledge the King had sought; but the King lay on his death-bed, and he had no time to read even that; and then the sage gave him the history of man in a single line; it was this: he was born, he suffered, and he died. There was no meaning in life, and man by living served no end. It was immaterial whether he was born or not born, whether he lived or ceased to live. Life was insignificant and death without consequence. Philip exulted, as he had exulted in his boyhood when the weight of a belief in God was lifted from his shoulders: it seemed to him that the last burden of responsibility was taken from him; and for the first time he was utterly free. His insignificance was turned to power, and he felt himself suddenly equal with the cruel fate which had seemed to persecute him; for, if life was meaningless, the world was robbed of its cruelty. What he did or left undone did not matter. Failure was unimportant and success amounted to nothing. He was the most inconsiderate creature in that swarming mass of mankind which for a brief space occupied the surface of the earth; and he was almighty because he had wrenched from chaos the secret of its nothingness. Thoughts came tumbling over one another in Philip’s eager fancy, and he took long breaths of joyous satisfaction. He felt inclined to leap and sing. He had not been so happy for months.

“Oh, life,” he cried in his heart, “Oh life, where is thy sting?”

For the same uprush of fancy which had shown him with all the force of mathematical demonstration that life had no meaning, brought with it another idea; and that was why Cronshaw, he imagined, had given him the Persian rug. As the weaver elaborated his pattern for no end but the pleasure of his aesthetic sense, so might a man live his life, or if one was forced to believe that his actions were outside his choosing, so might a man look at his life, that it made a pattern. There was as little need to do this as there was use. It was merely something he did for his own pleasure. Out of the manifold events of his life, his deeds, his feelings, his thoughts, he might make a design, regular, elaborate, complicated, or beautiful; and though it might be no more than an illusion that he had the power of selection, though it might be no more than a fantastic legerdemain in which appearances were interwoven with moonbeams, that did not matter: it seemed, and so to him it was. In the vast warp of life (a river arising from no spring and flowing endlessly to no sea), with the background to his fancies that there was no meaning and that nothing was important, a man might get a personal satisfaction in selecting the various strands that worked out the pattern. There was one pattern, the most obvious, perfect, and beautiful, in which a man was born, grew to manhood, married, produced children, toiled for his bread, and died; but there were others, intricate and wonderful, in which happiness did not enter and in which success was not attempted; and in them might be discovered a more troubling grace. Some lives, and Hayward’s was among them, the blind indifference of chance cut off while the design was still imperfect; and then the solace was comfortable that it did not matter; other lives, such as Cronshaw’s, offered a pattern which was difficult to follow, the point of view had to be shifted and old standards had to be altered before one could understand that such a life was its own justification. Philip thought that in throwing over the desire for happiness he was casting aside the last of his illusions. His life had seemed horrible when it was measured by its happiness, but now he seemed to gather strength as he realised that it might be measured by something else. Happiness mattered as little as pain. They came in, both of them, as all the other details of his life came in, to the elaboration of the design. He seemed for an instant to stand above the accidents of his existence, and he felt that they could not affect him again as they had done before. Whatever happened to him now would be one more motive to add to the complexity of the pattern, and when the end approached he would rejoice in its completion. It would be a work of art, and it would be none the less beautiful because he alone knew of its existence, and with his death it would at once cease to be.

Philip was happy.

Look Homeward, Angel (1929), Thomas Wolfe

Thomas Clayton Wolfe (1900-1938), not to be confused with a man of much lesser talents, Tom Kennerly Wolfe (Bonfire of the Vanities, Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test), was once an American household name famous for his vast, sprawling epics Look Homeward, Angel and Of Time and the River. Wolfe’s first novel, Look Homeward, Angel, was published in 1929, and his second novel, Of Time and the River, was the third bestselling book of 1935. Three years later, in 1938, Wolfe suddenly died of tuberculosis after delivering an enormous, unfinished manuscript to his new editor Edward Aswell. Following Wolfe’s death, Aswell, trimmed and shaped the manuscript, editing “perhaps one and a quarter million words, some five thousand pages, [and] over two hundred chapters” until he eventually extracted two novels—The Web and the Rock (1939) and You Can’t Go Home Again (1940)—both published posthumously under Wolfe’s name.

The death of Thomas Wolfe, a man whose monstrous vitality seemed to assure an almost mythical immunity to the passage of time, shook the literary world. Time Magazine remarked, “The death last week of Thomas Clayton Wolfe shocked critics with the realization that, of all American novelists of his generation, he was the one from whom most had been expected.” The New York Times dedicated a special obituary column to Wolfe, remarking

The death of Thomas Wolfe in his thirty-eighth year must be deeply regretted. His was one of the most confident young voices in contemporary American literature, a vibrant, full-toned voice which it is hard to believe could be so suddenly stilled. The stamp of genius was on him; though it was an undisciplined and unpredictable genius. He might have lived to become the best American novelist of his generation, and he might never have fought himself free of the chaos in which he lived and worked. There was within him an unspent energy, an untiring force, an unappeasable hunger for life and for expression which might have carried him to the heights and might equally have torn him down. Which it would have been, had have lived, no man can say.

With the publication in 1929 of his first novel, "Look Homeward, Angel," there could be no doubt that a new and powerful personality had appeared on the American literary scene. In a time when too many books are written out of a mere desire to write, here was a book by a young man who wrote because he must. ... Thomas Wolfe was above all a predestined writer, one to whom self expression was imperative. His first book proclaimed the fact, and those which followed confirmed it.

Today, Wolfe is all but forgotten. His triumphant 900-page hymn to America and immortal youth, Of Time and the River, is now lost in the depths of Amazon’s bestsellers list, ranking #511,382 in Books and #1,207 in Classic American Literature as of early 2024. Meanwhile, catamite erotica, The Song of Achilles, written by a woman with “long COVID” and chronic fatigue syndrome (I’m not making that up), ranks third in so-called Classic American Literature.

Wolfe’s decline, I believe, can only be attributed to the ascendency of academic ressentiment. In the hearts of scholars and readers today, there is no place for a man like Thomas Wolfe, a man “amorous of life” who saw beyond all the mournful faces and all the clouds of stirring dust and glimpsed the golden glory and the proud lonely grandeur of this earth.

I have much more to say on this, but now is not the time. I am preparing a much longer piece on Thomas Wolfe (hopefully coming in the next few weeks) in which these thoughts will find fuller expression.

More to the point:

Look Homeward, Angel was Thomas Wolfe’s debut novel composed while he was working as an English instructor at New York University. It was published in 1929 when Wolfe was 29 years old and it is an astounding novel of immense lyrical power. Wolfe’s boundless literary powers resist classification, and I can describe him only thus: he was an impassioned Whitmanian bard, a dreaming prophet, a romantic visionary, a demotic cataloguer, and perhaps above all, a son of the South searching for a hero and the “lost father of his youth.”

The novel follows a young Eugene Gant, the son of a stone carver, who spends his youth in the red hills of North Carolina until he is called away, out of warmth and plenty and into the unknown, into the strangeness of life and destiny. It is a tale of hunger, lust, rage, love, death, struggle, agony, hope, and dreams. It is the only novel I have ever read that captured so precisely what it is to be a young man full of hunger and wild hopes.

Excerpts:

. . . a stone, a leaf, an unfound door; a stone, a leaf, a door. And of all the forgotten faces.

Naked and alone we came into exile. In her dark womb we did not know our mother's face; from the prison of her flesh have we come into the unspeakable and incommunicable prison of this earth.

Which of us has known his brother? Which of us has looked into his father's heart? Which of us has not remained forever prison-pent? Which of us is not forever a stranger and alone?

O waste of lost, in the hot mazes, lost, among bright stars on this weary, unbright cinder, lost! Remembering speechlessly we seek the great forgotten language, the lost lane-end into heaven, a stone, a leaf, an unfound door. Where? When?

O lost, and by the wind grieved, ghost, come back again

[…]

Each moment is the fruit of forty thousand years. The minute-winning days, like flies, buzz home to death, and every moment is a window on all time.

[…]

he knew he would always be the sad one: caged in that little round of skull, imprisoned in that beating and most secret heart, his life must always walk down lonely passages. Lost. He understood that men were forever strangers to one another, that no one ever comes really to know any one

[…]

One by one the merciless years reaped down his gods and captains. What had lived up to hope? What had withstood the scourge of growth and memory? Why had the gold become so dim? AlI his life, it seemed, his blazing loyalties began with men and ended with images; the life he leaned on melted below his weight, and looking down, he saw he clasped a statue.

[…]

And he thought with pity of all the grocers and brewers and clothiers who had come and gone, with their perishable work a forgotten excre- ment, or a rotted fabric; or of plumbers, like Max’s father, whose work rusted under ground, or of painters, like Harry’s, whose work scaled with the seasons, or was obliterated with newer brighter paint; and the high horror of death and oblivion, the decomposition of life, memory, desire, in the huge burial-ground of the earth stormed through his heart. He mourned for all the men who had gone because they had not scored their name upon a rock, blasted their mark upon a cliff, sought out the most imperishable objects of the world and graven there some token, some emblem that utterly they might not be forgotten.

[…]

Of Time and the River (1935), Thomas Wolfe

Of Time and the River picks up where Look Homeward, Angel left off and resumes the tale of Eugene Gant. We follow him to graduate school at Harvard, to New York, and to France as he wanders across the world to hunt for love, fame, warmth, and the final door that opens wide, at last, to reveal his stony fate.

Excerpts:

Already the girl had been lost among the crowds of people streaming through the station, engulfed again in the everlasting web and weaving of this great earth, to leave him with a memory of another of those brief and final meetings, so poignant with their wordless ache of loss and of regret, in which, perhaps more than in the grander, longer meetings of our life, man's bitter destiny of days, his fatal brevity, are apparent.

And again the boy found himself walking along the platform towards the station after the departing people, whom he had met so briefly, and now lost forever. Again he had sought the mysterious promises of a new land, new earth, and a shining city. Again he had come to a strange place, not knowing why he had come.

[…]

For what are we, my brother? We are a phantom flare of grieved desire, the ghosting and phosphoric flicker of immortal time, a brevity of days haunted by the eternity of the earth. We are an unspeakable utterance, an insatiable hunger, an unquenchable thirst: a lust that bursts our sinews, explodes our brains, sickens and rots our guts, and rips our hearts asunder. We are a twist of passion, a moment's flame of love and ecstasy, a sinew of bright blood and agony, a lost cry, a music of pain and joy, a haunting of brief, sharp hours, an almost captured beauty, a demon's whisper of unbodied memory. We are the dupes of time.

We are the sons of our father, whose face we have never seen, we are the sons of our father, whose voice we have never heard, we are the sons of our father, to whom we have cried for strength and comfort in our agony, we are the sons of our father, whose life like ours was lived in solitude and in the wilderness, we are the sons of our father, to whom only can we speak out the strange, dark burden of our heart and spirit, we are the sons of our father, and we shall follow the print of his foot forever.

[…]

He prowled the streets of Paris like a maddened animal, he hurled himself at the protean complexities of its million-footed life like a soldier who hurls himself into a battle : he was baffled, sick with despair, wrung, trembling and depleted, finally exhausted, caught in the toils of that insatiate desire, that terrible devouring hunger that grew constantly from what it fed upon and that drove him blindly to madness. The hopeless and unprofitable struggle of the Faustian life had never been so horribly evident as it now was — the futility of his insane efforts to memorize every stone and paving brick in Paris, to burn the vision of his eyes through walls and straight into the lives and hearts of a million people, to read all the books, eat all the food, drink all the wine, to hold the whole gigantic panorama of the universe within his memory, and somehow to make "one small globe of all his being," to compact the accumulated experience of eternity into the little prism of his flesh, the small tenement of his brain, and somehow to use it all for one final, perfect, all-inclusive work, his life's purpose, his heart's last pulse and anguish, and his soul's desire.

[…]

He was conscious of a queer, bewildered and inappropriate feeling of surprise — a kind of numb, absurd wonder that if he had read all the books and poems in the world, and then tried to imagine for himself something as impossibly lovely as this girl and the whole scene around her, he could never, by any soaring stretch of the imagination, have come within a million miles of it.

[…]

And suddenly, all the horror, heat and desolation of the day was forgotten. He forgot the blind horror of the man-swarm thrusting through the mazes of the furious streets. He forgot the drowning flood of humid flesh, the pale, wet, suffering faces that thrust from nowhere out of sweltering heat, that were engulfed again into the heathazed distances of swarming streets in which man's life seemed more uncountable than the sands of the sea, and more blind, lost and horribly forsaken than the lives of those eyeless crawls and gropes that scuttle blindly and forever through murky ooze upon the sea's vast floor.

The old red light of evening filled his heart again with its wild prophecy, its huge and secret joy, and the great stride of oncoming night revived again, in all their magic, his childhood dreams of the enchanted city, the city of great men and glorious women, the city of unceasing joy, of power, triumph and success, and of the fortunate, good, and happy life.

Steppenwolf (1929), Herman Hesse

Steppenwolf relates the personal records of one Harry Haller, a lonely, solitary “hater of life’s petty conventions,” who considers himself to be half man, half wolf of the frigid steppes. Within Harry Haller, two personalities are locked in bitter strife: the wolf, full of passion and wild longing, who rages against a “toneless, flat, normal and sterile life,” and the man, a creature of taste and intellect who is content in a world of order, civility, books, and philosophy. Haller lives, for the most part, a quiet, cerebral life until one day he encounters a strange man who offers him a pamphlet entitled “Treatise on the Steppenwolf: Not for Everyone.” Inside, is a discourse on the nature of the human soul, which informs Haller that the distinction between the “dark world of instinct” (the wolf) and the lighter world of “tamed or sublimated nature” (the man), is entirely illusory. The soul does not consist of one primary distinction but infinite distinctions, infinite selves, and it is only through the embrace of the fluid self, the mutable, malleable, infinite soul, that one learns to renounce individual personality and unite in holy union with the transcendent “All.”

The treatise on the Steppenwolf leads Harry to a string of new acquaintances and lovers who invite him to explore the uncharted regions of his soul and examine the meaning of self and personality.

Excerpts:

… it had been just one of those days which for a long while now had fallen to my lot; the moderately pleasant, the wholly bearable and tolerable, lukewarm days of a discontented middle-aged man; days without special pains, without special cares, without particular worry, without despair; days when I calmly wonder, objective and fearless, whether it isn't time to follow the example of Adalbert Stifter and have an accident while shaving.

[…]

No stage was left for the noble and heroic heart. Nothing was left but the simple choice between a slight and swift pang and an unthinkable, a devouring and endless suffering.

[…]

Just as I dress and go out to visit the professor and exchange a few more or less insincere compliments with him, without really wanting to at all, so it is with the majority of men day by day and hour by hour in their daily lives and affairs. Without really wanting to at all, they pay calls and carry on conversations, sit out their hours at desks and on office chairs; and it is all compulsory, mechanical and against the grain, and it could all be done or left undone just as well by machines; and indeed it is this never-ceasing machinery that prevents their being, like me, the critics of their own lives and recognizing the stupidity and shallowness, the hopeless tragedy and waste of the lives they lead, and the awful ambiguity grinning over it all. And they are right, right a thousand times to live as they do, playing their games and pursuing their business, instead of resisting the dreary machine and staring into the void as I do, who have left the track.

[…]

Time and the world, money and power belong to the small people and the shallow people. To the rest, to the real men belongs nothing. Nothing but death." "Nothing else?" "Yes, eternity." "You mean a name, and fame with posterity?" "No, Steppenwolf, not fame. Has that any value? And do you think that all true and real men have been famous and known to posterity?" "No, of course not." "Then it isn't fame. Fame exists in that sense only for the schoolmasters. No, it isn't fame. It is what I call eternity. The pious call it the kingdom of God. I say to myself: all we who ask too much and have a dimension too many could not contrive to live at all if there were not another air to breathe outside the air of this world, if there were not eternity at the back of time; and this is the kingdom of truth. The music of Mozart belongs there and the poetry of your great poets. The saints, too, belong there, who have worked wonders and suffered martyrdom and given a great example to men. But the image of every true act, the strength of every true feeling, belongs to eternity just as much, even though no one knows of it or sees it or records it or hands it down to posterity. In eternity there is no posterity."

[…]

I had learned from her, once more before the end, to confide myself like a child to life's surface play, to pursue a fleeting joy, and to be both child and beast in the innocence of sex, a state that (in earlier life) I had only known rarely and as an exception. The life of the senses and of sex had nearly always had for me the bitter accompaniment of guilt, the sweet but dread taste of forbidden fruit that puts a spiritual man on his guard. Now, Hermine and Maria had shown me this garden in its innocence, and I had been a guest there and thankfully. But it would soon be time to go on farther. It was too agreeable and too warm in this garden. It was my destiny to make another bid for the crown of life in the expiation of its endless guilt. An easy life, an easy love, an easy death—these were not for me.

Narcissus and Goldmund (1930), Herman Hesse

Narcissus and Goldmund is perhaps Herman Hesse’s most enchanting novel. The story is set in Medieval Germany and follows the lives of two friends: the Apollonian Narcissus, a pious young novice at Mariabronn cloister, and Goldmund the dreamer, a sensitive young boy who flees Mariabronn to follow a white gypsy and the call of his pilgrim soul.

In the years that follow, Goldmund’s adventures are many. He becomes a tutor for the daughters of a wealthy knight, trains as a sculptor, escapes the black death, and at last, reunites with his oldest friend to share what he has learned of life, love, art, and death.

Excerpts:

“It was the overcoming of the transitory. I saw that something remained of the fool’s play, the death dance of human life, something lasting: works of art. They too will probably perish some day; they’ll burn or crumble or be destroyed. Still, they outlast many human lives; they form a silent empire of images and relics beyond the fleeting moment. To work at that seems good and comforting to me, because it almost succeeds in making the transitory eternal...The basic image of a good work of art is not a real, living figure, although it may inspire it. The basic image is not flesh and blood – it is mind. It is an image that has its home in the artist’s soul…”

[…]

Natures of your kind, with strong, delicate senses, the soul-oriented, the dreamers, poets, lovers are almost always superior to us creatures of the mind. You take your being from your mothers. You live fully; you were endowed with the strength of love, the ability to feel. Whereas we creatures of reason, we don't live fully; we live in an arid land, even though we often seem to guide and rule you. Yours is the plenitude of life, the sap of the fruit, the garden of pas-sion, the beautiful landscape of art. Your home is the earth; ours is the world of ideas. You are in danger of drowning in the world of the senses; ours is the danger of suffocating in an airless void. You are an artist; I am a thinker. You sleep at the mother's breast; I wake in the desert. For me the sun shines; for you the moon and the stars. Your dreams are of girls; mine of boys.

[…]

Only the life within him was real, the anguished beating of his heart, the nostalgic sting of longing, the joys and fears of his dreams. To them he belonged; to them he abandoned himself. Suddenly, in the middle of a page or a lesson, surrounded by his classmates, he'd sink into himself and forget everything, listening only to the rivers and voices inside himself which drew him away, into deep wells filled with dark melodies, into colorful abysses full of fairy-tale deeds, and all the sounds were like his mother's voice, and the thousands of eyes all were his mother's eyes.

[…]

He thought that fear of death was perhaps the root of all art, perhaps also of all things of the mind. We fear death, we shudder at life's instability, we grieve to see the flowers wilt again and again, and the leaves fall, and in our hearts we know that we, too, are transitory and will soon disappear. When artists create pictures and thinkers search for laws and formulate thoughts, it is in order to salvage something from the great dance of death, to make something that lasts longer than we do. Perhaps the woman after whom the master shaped his beautiful madonna is already wilted or dead, and soon he, too, will be dead; others will live in his house and eat at his table—but his work will still be standing a hundred years from now, and longer. It will go on shimmering in the quiet cloister church, unchangingly beautiful, forever smiling with the same sad, flowering mouth.

[…]

So many widely scattered places, heaths and forests, towns and villages, castles and cloisters, and people alive and dead existed inside him in his memory, his love, his repentance, his longing. And if death caught him too, tomorrow, then all this would fall apart, would vanish, the whole picture book full of women and love, of summer mornings and winter nights. Oh, it was high time that he accomplished something, created something, left something behind that would survive him.

Up to now little remained of his life, of his wanderings, of all those years that had passed since he set out in the world. What remained were the few figures he had once made in the workshop, especially his St. John, and this picture book, this unreal world inside his head, this beautiful, aching image world of memories. Would he succeed in saving a few scraps of this inner world and making it visible to others? Or would things just go on the same way: new towns, new landscapes, new women, new experiences, new images, piled one on the other, experiences from which he gleaned nothing but a restless, torturous as well as beautiful overflowing of the heart?

It was shameless how life made fun of one; it was a joke, a cause for weeping! Either one lived and let one's senses play, drank full at the primitive mother's breast—which brought great bliss but was no protection against death; then one lived like a mushroom in the forest, colorful today and rotten tomorrow. Or else one put up a defense, imprisoned oneself for work and tried to build a monument to the fleeting passage of life—then one renounced life, was nothing but a tool; one enlisted in the service of that which endured, but one dried up in the process and lost ones freedom, scope, lust for life. That's what had happened to Master Niklaus.

Ach, life made sense only if one achieved both, only if it was not split by this brittle alternative! To create, without sacrificing one's senses for it. To live, without renouncing the nobility of creating. Was that impossible?

Perhaps there were people for whom this was possible. Perhaps there were husbands and heads of families who did not lose their sensuality by being faithful. Perhaps there were people who, though settled, did not have hearts dried up by lack of freedom and lack of risk. Perhaps. He had never met one.

All existence seemed to be based on duality, on contrast. Either one was a man or one was a woman, either a wanderer or a sedentary burgher, either a thinking person or a feeling person— no one could breathe in at the same time as he breathed out, be a man as well as a woman, experience freedom as well as order, combine instinct and mind. One always had to pay for the one with the loss of the other, and one thing was always just as important and desirable as the other. Perhaps women had it easier in this respect. Nature had created them in such a way that desire bore its fruit automatically, that the bliss of love became a child. For a man, eternal longing replaced this simple fertility. Was the god who had created everything in this manner an evil god, was he hostile, did he laugh ironically at his own creation? No, he could not be evil; he had created the hart and the roebuck, fish and birds, forests, flowers, the seasons. But the split ran through his entire creation. Perhaps it had not turned out right or was incomplete—or did God intend this lack, this longing in human life for a special purpose? Was this perhaps the seed of the enemy, of original sin? But why should this longing and this lack be sinful? Did not all that was beautiful and holy, all that man created and gave back to God as a sacrifice of thanks spring from this very lack, from this longing?

Stoner (1965), John Williams

Ingmar Bergman once said, “I could always live in my art but never in my life.” I have often felt something similar—that I could always live in books but never in my life. Stoner is one of those havens of retreat, one of those blessed isles to which I often return when seeking some escape from the cold, gray, stasis of waking life.

Stoner has been called many things— a story about “work,” a novel about “love,”— but I maintain that it is, above all, a story about a quiet hero whose deep romantic longing for a life of beauty and passion found refuge and expression in the world of inner experience. Stoner teaches that within the depths of his heart, a man can keep something sacred, something that the world can never touch, never soil and profane. And even if this struggle be only in his solitary heart, even if his anguish and strife remain unavailing and the battle for the kingdom of man is lost, he shall know that his life, his experience, his inner world, was something precious, perfect, and rare.

The novel follows William Stoner, a simple “son of the soil” who leaves behind his life of dust and sweat for the trim, fine halls and stately porticos of the University of Missouri. Stoner abandons farming for a life of books and discovers that even in the stillest corners of the Earth, a man can live with a kind of private integrity and can keep himself amidst the straying world. He discovers that even a man raging in the dark can live with a kind of fierce intensity and solemn pride.

Stoner is an unheralded masterpiece and perhaps one of the world’s few perfect novels. But, as a professor of mine used to say, behind every unsung hero of the literary world is a name that resists mythology. “John Williams” is a humble, American, folkish name. It is not an elegant name in the way that fine delicate things like silver brooches and Venetian glass are good and elegant. It is a strong, sturdy name, like an old familiar hammer. But it is not romantic. It’s too rude, too American, too pedestrian. It lacks the Saxon strength of “W.B. Yeats,” the lustrous glimmer of “Evelyn Waugh,” and the aristocratic pomp of “F. Scott Fitzgerald.” It is not alluring and European like “Michel Foucault”, nor graceful and colonial like “Ralph Waldo Emerson.” Many fine things are spoiled by an unremarkable name. Indeed the worst part of Thomas Wolfe’s novels is the rather clumsy “Eugene Gant,” and I suspect too that Stoner would have found more acclaim had it not been burdened with the rather earthly and obscure “Stoner.”

Excerpts:

He had no friends, and for the first time in his life he became aware of loneliness. Sometimes, in his attic room at night, he would look up from a book he was reading and gaze in the dark comers of his room, where the lamplight flickered against the shadows. If he stared long and intently, the darkness gathered into a light, which took the insubstantial shape of what he had been reading. And he would feel that he was out of time, as he had felt that day in class when Archer Sloane had spoken to him. The past gathered out of the darkness where it stayed, and the dead raised themselves to live before him; and the past and the dead flowed into the present among the alive, so that he had for an intense instant a vision of denseness into which he was compacted and from which he could not escape, and had no wish to escape. Tristan, Iseult the fair, walked before him; Paolo and Francesca whirled in the glowing dark; Helen and bright Paris, their faces bitter with consequence, rose from the gloom. And he was with them in a way that he could never be with his fellows who went from class to class, who found a local habitation in a large university in Columbia, Missouri, and who walked unheeding in a midwestern air.

[…]

Stoner tried to explain to his father what he intended to do, tried to evoke in him his own sense of significance and pmpose. He listened to his words fall as if from the mouth of another, and watched his father’s face, which received those words as a stone receives the repeated blows of a fist. When he had finished he sat with his hands clasped between his, knees and his head bowed. He listened to the silence of the room.

[…]

Who are you? A simple son of the soil, as you pretend to yourself? Oh, no. You, too, are among the infirm—you are the dreamer, the madman in a madder world, our own midwestern Don Quixote without his Sancho, gamboling under the blue sky… But you have the taint, the old infirmity. You think there's something here, something to find. Well, in the world you'd learn soon enough. You, too, are cut out for failure; not that you'd fight the world. You'd let it chew you up and spit you out, and you'd lie there wondering what was wrong. Because you'd always expect the world to be something it had no wish to be. The weevil in the cotton, the worm in the beanstalk, the borer in the corn. You couldn't face them, and you couldn't fight them; because you're too weak, and you're too strong. And you have no place to go in the world.

[…]

You must remember what you are and what you have chosen to become, and the significance of what you are doing. There are wars and defeats and victories of the human race that are not military and that are not recorded in the annals of history. Remember that while you're trying to decide what to do.

[…]

“Lust and learning,” Katherine once said. “That’s really all there is, isn’t it?”

[…]

The love of literature, of language, of the mystery of the mind and heart showing themselves in the minute, strange, and unexpected combinations of letters and words, in the blackest and coldest print — the love which he had hidden as if it were illicit and dangerous, he began to display, tentatively at first, and then boldly, and then proudly.

[…]

Tentatively, clumsily, their hands went out to each other; they clasped each other in an awkward, strained embrace; and for a long time they sat together without moving, as if any movement might let escape from them the strange and terrible thing that they held between them in a single grasp.

[…]

It was a world of half-light in which they lived and to which they brought the better parts of themselves — so that, after a while, the outer world where people walked and spoke, where there was change and continual movement, seemed to them false and unreal. Their lives were sharply divided between the two worlds, and it seemed to them natural that they should live so divided.

[…]

“And so providence, or society, or fate, or whatever name you want to give it, has created this hovel for us, so that we can go in out of the storm. It’s for us that the University exists, for the dispossessed of the world; not for the students, not for the selfless pursuit of knowledge, not for any of the reasons that you hear.”

[…]

The Count of Monte Cristo (1846), Alexander Dumas

The Count of Monte Cristo has one of the most compelling and intricately crafted plots of all time. It chronicles the life of Edmond Dantès, a young sailor arrested the day before his wedding on false charges of treason. He is taken to a cliffside dungeon, the Chateau d’If, where he spends years plotting his escape and studying philosophy, art, and literature with a learned Abbé who occupies the adjoining cell.

When Dantès finally breaks free, he follows the Abbé’s directions to a secret cove, unearths a hoard of hidden treasure, and begins on his odyssey of revenge.

Note: You must read the unabridged edition which runs around 1300 pages. The older Victorian translations are excellent. The updated Penguin translation is disgusting filth unworthy of print—please do not read it. There is strong evidence that full-scale IQ has decreased since the Victorian era, so why would you willingly read something translated by a world-historical midwit?

No excerpts for this one— go read the book.

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/1184/pg1184-images.html#linkC2HCH0001

Naxos also has an excellent audiobook version read by Bill Homewood. I high recommend.

Conclusion:

I have read many books in my life. Most were an utter waste of time, and I finished them only so that I could denounce their authors with some degree of authority. I am too old for this now, and there are simply far too many good books to justify wasting time on these purely vindictive readings. I now abandon bad books as readily as possible. As Oscar Wilde once said, “To know the vintage and quality of a wine one need not drink the whole cask. It must be perfectly easy in half an hour to say whether a book is worth anything or worth nothing. ... One tastes it, and that is quite enough – more than enough, I should imagine.” To my taste, these are the finest liquors ever brewed. They are books that withstand a second, a third, a tenth re-reading, and in them you shall find a host of friends who can be summoned only with incense and lamplight and can never be found in that waking world of weary hours where time and pale faces move beneath a blank and pitiless sky.

See Caribbean Rhythms Episode 13 and Steppenwolf by Herman Hesse

Mishima: A Biography, John Nathan

Thank you for these great recommendations, I have accidentally stumbled into some of these.

One I also recommend is The Book of Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa. I find it fascinating -- not quite the same energy as the recommended texts, but well worth the read.

I do agree with Mr. Wobbegong -- that reading should not take the place of doing; that it is often enough for one of one's friends to have read some of the books above, and to have borrowed from it the needed energy to accomplish in this world; he who has a fire lit within him freely shares it with those he loves.

Only a small number of us need to read these books to really perform in their spirits -- the goal has always been contagion.

Dear author,

I have often wondered whether many who read should stop reading and start doing.

It seems to me that many Sensitive Young Men fit this mold.

It seems these texts you describe would help the reader not only clarify his inner confusion and self-understanding, but might also spur him to some sort of productive action in the world.

In other words (I promise I don’t mean the following question churlishly): what will these books help me do to help Life and Truth win out?